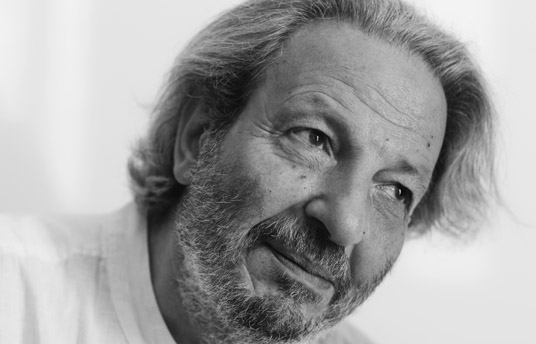

People in Film: Mohamad Malas

Oct 01, 2013

The Doha Film Institute caught up with master Syrian director Mohamad Malas at TIFF last month, where his newest film, ‘Ladder to Damascus’, had its world premiere screening. Taking place almost entirely inside a lovely old house in the Syrian capital, the film examines the ongoing insurgency from the point of view of 12 characters who represent a microcosm of Syrian society.

Doha Film Institute: One of the most striking things about your film, of course, is that the audience is isolated inside the house along with the characters. We are always at a remove from those events of the insurgency that take place over the course of the film. Why that structure?

Mohamad Malas: First of all, it’s a cinematic and a dramatic choice. I chose to tell the story when the bombing and everything was a bit far from Damascus. Cinematically, I chose to stay inside the house because television and other media were showing what was going on outside and I wanted cinema to be different, to show what’s happening inside. From a logistical point of view, as one of the characters in the film says, it’s impossible to film outside because anyone seen with a camera will be killed.

DFI: The main character’s nickname is ‘Cinema’, so in effect you’ve got cinema living inside this house. This points to the question, What do you think the role of cinema is in a situation like the one in Syria at the moment? Cinema vs. television is one thing, but what do you think cinema can and should do in a moment like this?

MM: Throughout its history, Syrian cinema has been one of the most heavily censored media; it has been very difficult to make films. When the Ba’ath regime came to power in 1963, they decided to put cinema under [a public, government-controlled institution] to turn out propaganda. A few Syrian filmmakers have tried over the last 35 years to break through this censorship and be able to show the real situation of society, the real lives of people in Syria. Sometimes they succeeded; sometimes it was impossible. I myself have had many projects that I was unable to make – even though the movies were not ideological or political, the regime felt that they were against their ideas so they were prohibited. Since 1998, I have decided to stop working with the National Film Organisation in Syria and try to make films that are independent, and I succeeded. That’s why in ‘Ladder to Damascus’, cinema is celebrated as a medium of expression.

DFI: This was a very dangerous film to make, both physically and ideologically. Will it be seen in Syria?

MM: Before shooting a film, we know there is a risk that the film won’t be distributed outside Syria. And in Syria, we don’t have good theatrical distribution. Syria is only producing one or two films a year, which is a very low number – and these few films are produced by the National Film Organisation, who censor the film from script to final product. Even though these films are produced by the government, they are not distributed in Syria because we don’t have the cinemas.

DFI: So they are just for export?

Christian Eid (interpreter): They are just for TV I guess?

MM: If the government is happy with the film, they send it abroad to festivals, but they are not usually distributed for public screenings, only festivals and cultural events.

DFI: Watching this film is a bit like watching a dream. Part of this is the way the performances are handled. It’s hard to find the right word – they are not theatrical, but they are presentational, as though they are being given to the audience. Was this a very conscious choice?

MM: I like this feeling, because dreams are my first source of cinema. Dreams tell me how to choose locations, lighting and such. I have made a film called ‘The Dream’, and wrote a book called ‘The Dream’ as well. The acting style was very much a choice. The film is telling of an event that is happening now, one that is not yet complete. I was living and feeling these events – and the characters, the actors are feeling it too, because their stories are very real. The actors are playing their own stories – that’s why the names of the characters are the same as the names of the performers. The dialogue I had with them let me make this choice to have this kind of confrontation between the characters and the spectators – because still today, we don’t know what will happen.

DFI: When everyone who lives in the house is introduced early in the film, I had this odd feeling: I wanted the film to be a musical.

MM: Well, why not? But whatever the feeling you as a spectator has, I’m not going to take you to the place you want to go. You may imagine the film is going to become a musical … but then that stops. It’s like a dramatic, cinematic game between the spectator and the director.

DFI: Is the film fully scripted, or improvised, or a bit of both?

MM: I wrote a script, but before the uprising began. That was the script I presented to the authorities. Suddenly the events of the uprising started happening in the streets, so I had a choice: wait for the situation to be done and film the script as it was, or film immediately with some changes to the script. The house and the characters were already in the original script, but they were living a sort of oppressed life and of course the revolution was not present. When I started talking to the characters, to the actors, I felt they had something to say about the events of the insurgency. I decided that every actor should play themselves.

DFI: What happens now, when you go home?

MM: I think it will be impossible to get a screening permit for this film in Syria. When the government authorities watch the film, they are going to put a black mark against everyone who participated in making it, because the situation is extraordinary – the government is of course busy with military action. If things were normal, I’m sure there would be an investigation into all the people who worked on my film.

DFI: Very brave.

MM: Yes, of everyone.