Islam in Film

Jun 30, 2013

By Abbas Moussa

Translation by Ourouba Hussein

The rise of Arab cinema during the last century was marked to a certain extent by an inclination for religious films, for which the 50s are considered the golden age. Despite the popularity of this type of film at that time, unfortunately few have remained in the collective memory, or left any significant impact whatsoever on Arab or international cinema.

Islam-themed films usually revolve around a religious figure’s biography, historical events of Islam, or a story that sheds light on Islamic values and morality. Ibrahim Ezzeddin’s ‘The Advent of Islam’ (1951) is generally considered to be the first Arab religious picture, and was followed by films including Ahmed Toukhi’s ‘The Victory of Islam’ (1952) and ‘Bilal the Prophet’s Crier’ (1953); Hussein Sidqi’s ‘Khaled bin Alwaleed’ (1958); Ibrahim Alsayyed’s ‘Allahu Akbar’ (1959); Niazi Mustafa’s ‘Rabia Aladawiya’ (1963); Ibrahim Amara’s ‘The Migration of the Prophet’ (1964); Salah Abu Seif’s ‘The Dawn of Islam’ (1971); and the noted ‘Mohammad Messenger of God’ (1976) by Mustafa Alaqqad.

In addition to these religious films, other historical films with a religious feel emerged, such as Yussif Shahin’s ‘Alnasser Salahuddin’ (1963), The film tells the story of a period in the life of the leader Salahuddin Alayyubi, during the crusades, when Salahuddin attempted to prove that Jerusalem is a holy place for Muslims.

To some extent, these films have much in common. Sets, costumes, narration and characters are very similar among them. Representations of infidels and Gentiles are similar in terms of their physical ugliness, their cruelty, debauchery and immorality, as well as their brutality toward women and society at large. On the other side, early Muslims were shown as undernourished and brutalised, good-looking and with high standards, and always turning to Allah as their saviour. Some directors overemphasised these traits; the result was monotonous stories and weak performances.

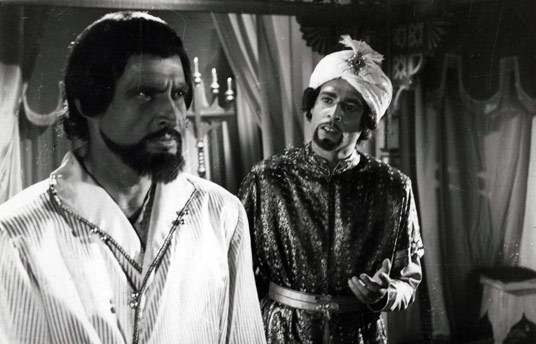

Yussif Shahin’s ‘Alnasser Salahuddin’ (1963)

In addition, filmmakers often worked with the same group of actors to make these many religious films. This meant many repeat appearances for stars, as was the case for the actor Abbas Farhat, who appeared in ‘The Advent of Islam’, ‘The Victory of Islam’, ‘House of God’ and ‘Khaled bin Alwaleed’; Hussein Riad appeared in ‘Bilal the Prophet’s Crier’, ‘House of God’, ‘The Martyr of Divine Love’ and ‘Rabia Aladawiya’. Actress Majida appeared in ‘The Victory of Islam’, ‘Bilal, the Prophet’s Crier’ and ‘The Migration of the Prophet’. Needless to say, these repeated appearances confused viewers, given that the same actors appeared in very similar films, sometimes performing entirely different characters.

Religious Restrictions

These films encountered a good deal of restriction on religious grounds. For various reasons, filmmakers could not highlight certain of the merits of a given historical character, and there were some events that could not be portrayed. This came about by the various disputes that surround the events and characters of the history of Islam. Some believed traditional representations of characters must not be altered, even for the sake of dramatic needs. Others believed the opposite: that changes were needed to meet the requirements of the script.

Religious restrictions also play a role in limiting representations onscreen, especially as it is forbidden in Islam to depict the Prophet Muhammad or the Ten Promised Paradise. Filmmakers wanting to tell these stories had to resort to other means than putting actors in front of the camera. In films revolving around the Prophet Muhammad, for example, no actor performed his character. This was a tough mission: the question was, How can we produce a two-hour film about a character who cannot appear onscreen? Various options were available – from creative narration techniques, to dialogue between the characters – but these generally had the effect of reducing the impact of the present-yet-absent central character.

Nevertheless, some filmmakers succeeded in producing powerful films working within these strict boundaries.

The Prophet Muhammad is the most important figure in Islam. In the context of not being allowed to represent the Prophet onscreen, acclaimed filmmaker Mustafa Al-Aqqad, director of ‘The Message’, said, ‘In “The Message”, we face a great obstacle, which is to unveil the images of the Prophet and the Four Ancestors. We couldn’t show their images, voices or shadows, because this is so sensitive for Muslims. It is very difficult to talk about a main character in a script without showing him, especially given how used Western audiences are to seeing their heroes in films. We chose Hamza to help narrate our story, but unfortunately he was killed early in the story, which left a big gap.’

Only a limited number of these religious films succeeded in having an impact on international screens; most religious and Islamic films produced in the Arab world remained very much within it. ‘The Message’, however, is a different story. The director wanted to reach out to the West in its own languages and not rely on translation, considering direct interaction between the film and its audience is better.

‘The Message’ was released in an Arabic version, with Abdullah Gaith as Hamza; the English-language version features Antony Quinn in the same role; Mona Wasef and Irene Papas played the role of Hind in the Arabic and English versions respectively. The production cost of the two versions was estimated at $10 million; the English version earned 10 times more than the film’s cost. ‘The Message’ was translated into 12 languages and nominated for an Academy Award for best music.

With the Holy Month of Ramadan around the corner, now is an excellent opportunity to have a look back at some of these films and perhaps enjoy some of the creativity filmmakers employed to bring the stories of Islam to the world.