DFI Film Review: Breathless

Feb 04, 2013

By Alexander Wood

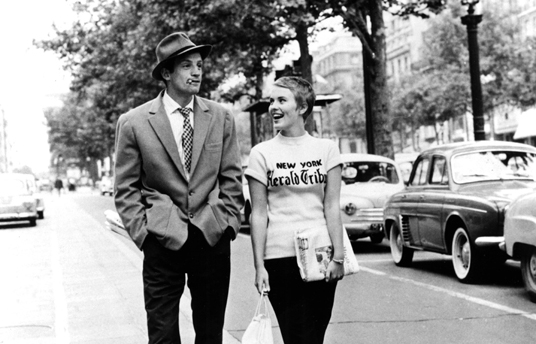

The tones of cool jazz spill out of the film as a Parisian gangster lights the first of many cigarettes and motions to steal the car of an unsuspecting tourist. While on his joyride he discovers a revolver in the glove box that allows him to evade police, yet makes him a wanted man. Amidst the turmoil of life on the run, Michel Poiccard (Jean-Paul Belmondo) romances women with his abrasive charm and manages to be enthralled with Patricia Franchini (Jean Seberg), a confident journalist from New York. The unconventional love story to follow is set against the beautiful landscape of Paris while revealing a world of violence and crime hidden beneath the surface.

Classic framing, lap dissolves and close-ups of characters sets the tone of film and offers clean and engaging cinematography. Shortly after stealing the car the troubled anti-hero, Michel, revels in the French countryside as he heads to an unknown destination. While discussing the beauty of the landscape with himself, Michel turns to the camera and says, ‘if you don’t like the shore, if you don’t like the mountains, if you don’t like the city, then get stuffed’. By speaking directly to the camera he is acknowledging the presence of the audience and sutures them into the film. This technique of breaking the fourth wall, the barrier that divides the audience and actors, is more often associated with modern films like ‘Ferris Beuller’s Day Off’, ‘High Fidelity’, ‘The Big Lebowski’, and ‘Fight Club’. By making the audience aware that characters are acknowledging their presence, it disrupts the reality of the world that the film is attempting to capture.

The use of this technique makes sense, considering that Patricia is in a constant state of questioning her own reality and purpose in life and love. Patricia’s existential attitude is shown in her confusion in the face of an apparently absurd world, and her struggle to stay with Michel or leave. In one scene she states, ‘I want to think about something, but I can’t seem to’, demonstrating her struggle to make sense of, and communicate with the world around her. Existentialism was developed by French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, who believed that there is no such thing as good and bad, rather what happens—happens. This way of thinking is a fitting perspective for Michel, considering how easily he kills a police officer and steels money from countless people. Blurring the lines of good and bad, self and the other, is unique part of the relationship that Michel and Patricia share—and ultimately allows their strange and existential love affair to continue. Another key element of Sartre’s existential thinking is that people can create their own values and meaning in life. Michel is the perfect example of this, creating his own moral code and narrative to suit whatever stolen car he is driving.

Meaning in any film is formed by linking individual scenes together to create a narrative. Throughout Jean-Luc Godard’s ‘Breathless’ there are numerous scenes that use jump cuts to purposely break the flow of the cinematography, leaving information out and creating a choppy sense of time. An example of this type of editing is seen when Michel is complementing Patricia in the car, and the camera captures many elements of their conversation. By capturing multiple angles and lighting conditions in quick succession it creates multiple readings of the same subject, allowing viewers to develop their own individual reading of each scene. Much like Sartre’s existentialism, the film allows people to forge their own meaning of the world they see. Another element of filmmaking that adds to viewer’s perception of reality within the film is the Iris fade in: a type of transition that slowly darkens the scene as if the audience is closing their eyes. The use of this technique however, disrupts the reality of the film by reminding the viewer that they are in fact, watching a film.

Despite the many elements that add to the cinematography of the film, the relationship that Michel and Patricia share is undeniably unique. Throughout the film both characters struggle with ideas of love and affection. Michel’s complements are often accompanied by some sort of playful insult and plea for Patricia to join him in Italy. Bantering back and forth whenever they are together, Michel an Patricia question whether they love each other, their path in life and ultimately if they will leave France to begin a new life. Early in the film, Patricia says that she wants them to be like Romeo and Juliet, Michel of course dismisses such a statement and continues his attempts at flattery. However, what Michel doesn’t know, is that the comment is foreshadowing the end of their relationship.

Having evaded the police, convinced Patricia of his love and acquire the money needed to escape to Italy, it would appear that the two characters will live happily ever after—unfortunately, this is not the case. In the end, Patricia having realised her love for Michel, calls the police to ensure that the two will be separated. The outcome however, is closer to the tragic ending of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, with Michel dying on the street as a result of his love for Patricia and a gunshot wound. The final scene shows Patricia looking straight into the camera, mimicking how Michel would caress his lip. She turns away from the camera, and at that moment the film ends.

The tragedy and humor bestowed upon this unconventional couple is evident from the first scene to the last and offers audiences a new type of love story; one which lives and dies in beautiful turmoil.